Ice Age Trail in Northern Wisconsin: Bouldery Moraines and Pit-and-Mound Microtopography

Sep 26, 2021 • Joe Mason

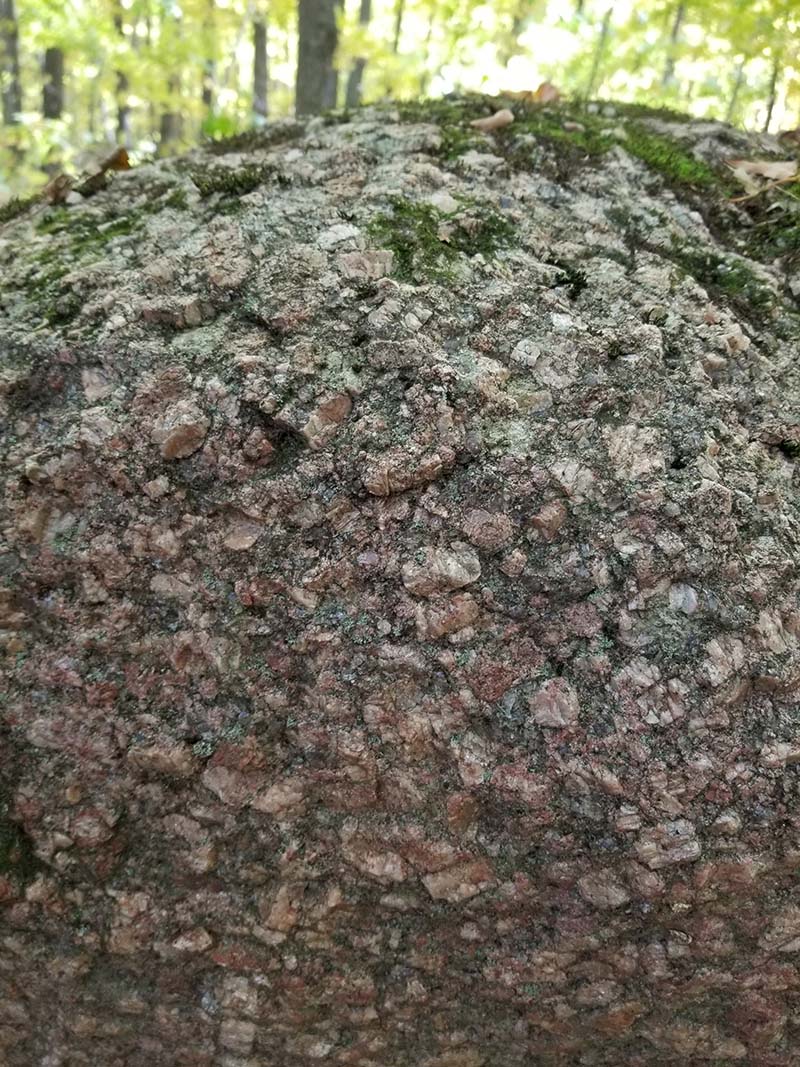

I have been walking the Ice Age Trail in Wisconsin, segment by segment since 2017. The trail follows former ice sheet margins cross the state, often in hilly topography with stony soils that were never farmed, or farmed only in patches. In southern Wisconsin, especially in the southern Kettle Moraine, the trail goes through many areas that were once savannas or prairies but have filled in with trees since the nineteenth or early twentieth century. In northern Wisconsin, most of the rugged moraines the trail follows has been forest since the end of the last glacial period, but the forest there now still reflects the legacy of the logging era, beginning in the 1850s-1860s and continuing into the early 20th century, often with more selective cutting up to the present. These forests are often dominated by relatively young trees, with more sugar maple than in many pre-settlement forests. They are still beautiful forests to walk through, however! The boulders that the trail crosses over reflect the bedrock the ice was eroding farther up its flowpath. In Marathon and southern Langlade counties, many of the boulders are distinctive Wolf River Granite, like the ones below on the beautiful Plover River segment.

A wind storm tipped hundreds of trees along the Ringle segment earlier this summer, pulling up whole soil profiles in their roots. Over time this process affects most of the forest floor on northern Wisconsin moraines, and occasional freshly thrown trees are common everywhere along the trail (also true of the northern Kettle Moraine).

Over time (decades or more), the soil falls or washes off the roots, and the roots and trunk decompose. This leaves paired pits and mounds of soil. The first photo below shows a pit-mound pair. If you look carefully you can still see part of the trunk of the tree that tipped, to the left of the mound. The mounds are often preferential locations for new trees to grow, including the big white pine on a mound in the second photo. Both photos are from the Wood Lake segment of the trail, in Taylor County.

Over even longer time periods (hundreds to thousands of years), repeated tree throw creates pits and mounds across much of the forest floor. This is often called pit-mound or cradle-knoll microtopography, and is especially visible in this photo from the Wood Lake segment because of the scarcity of shrubs in the understory and the uniform carpet of sedges.